Cashing in at Art Basel By William Dowell, June 2012 |

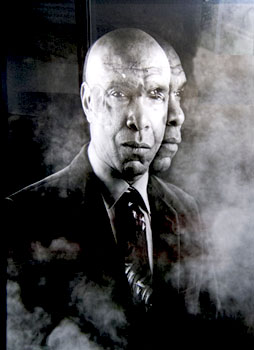

Rashid Johnson's portrait of an African American's split identities |

$78 million for a 1954 painting by Mark Rothko?

At a first glance, the eurocrisis and impending financial apocalypse seems barely credible once you have been to an extravaganza like Art Basel.

But first impressions can be misleading. The fact is that with the euro's future in doubt, and the US dollar fast evaporating, Basel, which specializes in masterpieces of modern and contemporary art, offers the world's desperate rich a last safe haven for vanishing wealth.

|

These days a Rothko may be more of a sure fire bet than the Swiss Franc. The rich, in case we hadn't noticed, live in a different world from ours, and Art Basel revealed for just a few brief moments just how different it really is.That is not to underestimate the importance of art. A masterpiece can delight and energize our imagination, or it can change the way we understand life and in the process sensitize us to existence. From that perspective, it is one of the most valuable pursuits that occupy human existence. It is not hard to understand why powerful personalities from kings to princes, dukes and popes covet the creative genius of a Michelangelo, Leonardo, a Picasso, or a Miro. Leaders are expected to know more than the crowds that follow them, and artists are often in the vanguard. The art market is essentially an attempt to buy greatness as well as culture, and consequently to own part of the fabric that ties civilization together. Pretenders to true power, who cannot afford the world's greatest creative geniuses, are forced to settle for the work of lesser craftsmen, and that creates a hierarchy, which in itself becomes a symbol of power and wealth.

In the end, the work itself as well as the price paid for it becomes a seemingly indelible symbol of power and that gives it monetary value as a sort of currency in itself. The global art market is now estimated at more than €46 billion.

Basel is where all this plays out with enormous finesse, and the formula has worked so well that Art Basel has created subordinate satellite shows. Today, there is an Art Basel-Miami, and just this year announced a new Art Basel-Hong Kong (In case anyone hadn't noticed, power these days is shifting to the East).

Art shows like Germany's Documenta try to explore what is new in contemporary art today. In contrast, Art Basel is basically about money and power. While much of what is new is now coming from Asia, Africa and Latin America, Art Basel remains firmly implanted in the West. At this year's Documenta, only 9% of the work shown was from the US. A rough survey of Art Basel carried out by Art News reported that 23% of the work was American, while just over half that amount, 12%, came from Germany and another 12% came from Britain. Switzerland, France and Italy shared 18%, or roughly half as much each. China and Africa accounted for under 2% each.

If the purpose of Art is to expand the imagination and explore new perspectives, Art Basel takes no chances. The revolutionary insights it presents have for the most part already been certified as being a safe investment at countless auctions. This is the place to go if you want to see which works by Picasso, Kandinsky, Max Ernst, Miro and the other 20th century greats are still available. Each of these masters pushed the limits of imagination, but they did it so long ago that there is no longer any risk to the establishment that they will upset the existing order. They are, in fact, part of the existing order.

|

One gallery estimated the value of the works on display in its space at a quarter of a billion dollars. The show presented 2,500 works. At least 1,000 galleries had applied for space. Art Basel allowed only 300 to exhibit. The show was strictly hierarchical. The best known and best selling artists were presented on the ground floor at Art Basel itself. The ones who were almost as good were shown on the second floor. More experimental work was relegated to a gigantic hangar-like building next door and dubbed, "Art Unlimited."

Galleries that couldn't make it into the real Art Basel displayed their works at a satellite show, Scope, which was within walking distance. Students and beginners, who hoped to make it one day, were at an even more obscure location at a show labeled "Liste 17."

To safeguard the wealthiest collectors from having to rub shoulders with the ordinary public, Art Basel reserved the first two days of the show to collectors by invitation only. Much of the most sought after work disappeared before the larger public had a chance to see it. Nevertheless roughly 65,000 people spent CHF 45 for a ticket to see what was left.

One art review referred to the show as a "flea market for art," and in fact one of the challenges at Art Basel is to distinguish the watershed achievements from soon-to-be-forgotten pretentious attempts to provide meaningful insight. Phillip Guston's painting, "Orders," kicked off the race when it was snapped up for a mere $6 million.

|

One of the most eccentric pieces was Austrian artist, Franz West's gigantic sculpture of huge, twisted metal pipes, painted pink to resemble a section of intestines pulled from a giant. In case anyone missed the point, the work was entitled "Gekroese," German for "bowel." Too large to fit anywhere except in an outside garden or field, West's creation reportedly went for more than a million dollars.

In the end, Mark Rothko's "Untitled" didn't sell for $78 million at Art Basel, but the curators of a private collection asked to place it on reserve and two other collectors expressed firm interest. A less ambitious sculpture of an unidentified anorexic figure arching its back in apparent agony by Louise Bourgeois went for a reported $2 million. Compared to that, Cindy Sherman's new series of photographs of herself, "Untitled," 2010-2012, which sold four out of six copies for $450,000 each, seemed like a bargain.

What does all this have to do with Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and the fact that the euro seems condemned to finish its career on life support? Having been submerged for the last several months in dire reports of impending doom, it may be worth remembering that there is still enormous wealth in Europe--more than enough to guarantee a comfortable lifestyle to all of its inhabitants. But Basel's second lesson is that in contrast to the post-war era when we looked at society as a community, the wealthy these days are increasingly isolating themselves from the rest of society.

Great art may be priceless, but is it really worth the human misery that follows the financial collapse of a society itself. E pluribus Unum may be a New World concept, but the age-old question: Am I my brother's keeper? still applies. What priority does a sense of community and commonality really take in the imagination of the collectors clustering at Art Basel? Are we like a modern-day Nero, playing the violin while Rome burns?

Centuries ago the nobility press ganged soldiers into extracting wealth in the form of taxes from ignorant serfs. Today the wealth that dissipates itself in luxury is extracted from the helpless masses in the form of VAT, endless red tape and elaborate schemes for tax evasion. As always, the strategy is manipulated behind behind closed doors by politicians, lawyers and bankers. Instead of the prince's henchmen, it is private security services that protect the elite from the angry masses. The formula remains the same though. Art Basel's message to the desperate public in Greece and Spain as well as to the failing euro, is, to paraphrase Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind, simply a matter of: "We have ours, and frankly, my dear, we don't give a damn about yours."

The point is not that we should stop spending on art, but it is rather that we should not forget the other aspects of our civilization that also require attention. Even the rich cannot survive for long if isolated from the community at large, and with their privilege they have a special responsibility to see that that community survives. As John Donne put it in a letter to a friend, "No man is an island entire of itself. Every man is a part of the continent. If one little clod be washed away, Europe is the lesser because of it. Ask not for who the bell tolls; it tolls for thee."