| Jill Seaman Stops Kala Azar and Saves the Nuer by William Dowell [This piece ran in TIME's Heroes of Medicine, 1997] |

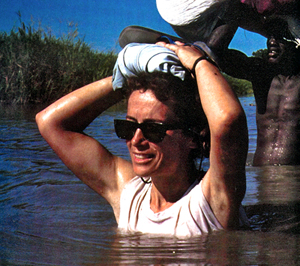

Jill Seaman makes her rounds in southern Sudan |

Aviation maps list Duar, a sprawling agglomeration of African huts called 'tukuls,' as "Dwil Keil," the 'lone house. The name is an ominous reminder of the recent past.

Not long ago, Duar, in south Sudan's Western Upper Nile province, found itself at the epicenter of one of the deadliest and least publicized epidemics to hit Africa this century. Of the more than 1,000 original inhabitants, only four were left alive. And that was just the beginning. More than 100,000 people died in the surrounding region. The Nuer, south Sudan's second largest tribe, faced certain extinction.

The cause of this destruction was kala azar, scientifically known as visceral leishmaniasis, a deadly parasitic protozoa only slightly larger than ordinary bacteria, and carried by the bite of a sand fly that is less than 2-mm long.

Even by African standards, kala azar is a frightening disease. It coats itself with a protein that makes it inoffensive to the body's defenses and then invades white blood cells. Its host's immune system is left in a shambles. To make matters worse, kala azar stimulates bone marrow to produce white blood cells so rapidly that they do not have a chance to reach full strength and are unable to defend themselves against disease. Usually, a second infection, such as pneumonia, malaria or anemia, brings painful death.

If it had not been for the single-minded, and often heroic, intervention by the Dutch branch of Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors without Borders), Sudan's epidemic of kala azar might easily have turned into a modern-day version of the Black Death, the plague, which ravaged Europe in the middle ages. MSF was not only largely responsible for bringing the epidemic under control, but in the process it redefined how medicine is done in the field.

The driving force behind this effort was an unassuming, but iron-willed young American woman from Moscow, Idaho, Dr. Jill Seaman. Her previous specialty had been providing public health to Yupick Eskimos in the Alaskan bush. In an eight-year struggle against kala azar, she developed more clinical expertise with more patients suffering from the disease than any other single doctor in history.

The disease Jill Seaman battled is not new. Kala azar ravaged much of eastern India in the last century, where it earned its name, which means "black fever" in Hindi. In 1901, a British physician, Dr. William Boob Leishman, developed a stain to detect the parasite with a microscope, and Dr. Charles Donovan showed that specimens could be extracted directly from the spleen. The parasite is now called Leishmania donovani in their honor. Variants of leishmaniasis are found in southern Europe, South America and even Texas. A complex treatment involving daily injections of a toxic heavy metal, pentavalent antimonial, which is marketed under the trade name Pentostam, has been available since the 1930s. But kala azar continues to fascinate medical researchers. Parasitologists often become so obsessive that they call themselves Leishmaniacs.

Although the epidemic in Sudan involved a disease that was already well studied, the reaction to it in Sudan was delayed because few of the people who came in contact with it in the field had enough medical knowledge to recognize what they were seeing. The western Upper Nile is one of the most remote areas in the world. It has almost no roads. The Nuer tribesmen who populate it, have little contact with the rest of the world. To make matters worse, the fundamentalist Islamic government in Khartoum, engaged in a civil war with the black Christian and animist tribes of the south, showed no interest in stopping a disease that might prove more effective at quelling rebellious tribes than sending in armed troops. In 1988 when the epidemic was just beginning to spread, Khartoum banned relief flights into the south, and the UN anxious to keep some rapport with Sudan's increasingly erratic government, asked all western relief agencies to stay out. As late as 1992, a World Health Organization representative in Khartoum tried to argue that no epidemic had ever existed.

MSF was one of the few organizations that refused to listen. MSF already had a medical team in Khartoum. In the summer of 1988, it sent a second team clandestinely into the south. In the spring of 1989, the team began to hear reports of a strange new "killing disease." MSF doctors in Khartoum thought it might be kala azar. They had already begun treating several hundred Nuer tribesmen who had fled north to the capital.

By then, Jill Seaman was attending classes at London's School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Four years earlier, she had taken a break from her job with Eskimos to work with Ethiopian refugees at a camp in Sudan. She was frustrated by the lack of microscopes at the camp, but she also realized that even if she had had one, she wouldn't have understood what it was that she was looking at. She needed more training, and London was recognized as the place to get it. It turned out that she loved the classes. When MSF came to the school looking for a doctor to take on kala azar in the bush, she signed up immediately.

There had been a debate inside MSF as to

whether kala azar could be handled in the bush on the scale that the Sudan operation was going to require.

"Kala azar had always been treated in hospitals, and then only a few cases at a time," says Johan Hesselink, who headed MSF-Holland's south Sudan operations during that period. "We were going to be dealing with thousands of patients at a time, and we didn't know if it would be possible to do this out in the open and under a tree."

When she finally reached Sudan, even Jill Seaman wasn't sure what she had signed on for. "My legs swelled up to twice their size with mosquito bites," she says,"and I was ready to cut my contract short by 11 months." But she was clearly captivated by the place and by the enormity of the human catastrophe. "If you witness a tragedy like that, how can you not be moved?" she says. "Where else in the world could 50% of a population die without anyone knowing? "

The first step was to find out exactly what the disease was doing. The team had set up operations in a village called Ler, several days' walk south of Duar, the center of the epidemic. Jill Seaman and a handful of Nuer staff began to explore on foot to the North. What they found was chilling. In some villages, cows wandered unattended. The entire human population had died. The Nuer who did survive looked like walking skeletons. Sick children carried starving babies after their parents had died on the road.

"Everywhere I went, people were dying of kala azar," Jill says. "I was certain that we had a serious problem."

The level of infection from villagers was so high, that one lab changed its readings of blood tests because it didn't believe the results it was seeing were possible.

With the infection rate increasing, Jill asked for an entomologist to pin down the vector. MSF sent Judith

Schorscher, a Canadian, based in Paris. She spent six months with special boxes equipped with fans designed to suck insects into traps where they could be dissected and analyzed. Volunteers agreed to be bitten, while Jill and the others trapped the insects in small blow-pipes, killed them with a puff of cigarette smoke and dissected the infected organs under a microscope.

It soon came apparent that the vector was the female sand fly, phlebotomus orientalis, found in the region’s vast acacia forests. The tiny insect can only fly 200 feet a day and to a maximum height of 6 feet, but it had begun to encounter refugees escaping into the forests from areas where kala azar was already endemic. The parasite multiplied in the pharynxes of sandflies who had bitten an infected person. The sand fly was immune, but the parasites multiplied so quickly that they eventually nearly strangled their host. When the sandfly tried to bite its next victim, it cleared its throat by spitting a small plug of parasites into the wound it had just opened. Only this time the human victim had no natural resistance to the parasite. The cycle amplified the disease with victims and sandflies receiving stronger and stronger doses as the parasite encountered fresh hosts.

After the early surveys, Jill Seaman was determined to set up operations in Duar. Johan Hesselink, MSF's country manager at the time thought she was crazy. He would never be able to get a plane in to evacuate the staff in the event of trouble. Jill went over Hesselink's head, and appealed to MSF's managers in Holland. Hesselink was furious, but eventually he had to admit that she was right. He warned Jill that if she ran into trouble, she might have to walk out on foot. Flights were often spaced up to six weeks apart. Cargo on the planes was so limited that the staff frequently had to decide between food and medicine. "We saw relatives losing weight because they were giving their food to sick family members," says Sjoukie De Wit, a Dutch nurse who became Jill Seaman's sidekick. The doctors decided that they did not need to eat that much, when the Nuer were starving.

There were plenty of reasons for feeling emotional stress. The original MSF site at Ler was bombed on Christmas day in 1989 while Jill was still there, and again in October 1990 after she had moved to Duar. She got the news of the second bombing by radio from a pilot who was evacuating all but two expats from Ler. Then the radio went dead. "I guess you felt kind of isolated," she says. Khartoum went on to bomb every relief site in the south that year. The message was clear, but the rebel forces were not much better. In November 1991, Ler was overrun by an opposing faction. Jill watched as rebel troops moved through Duar on their way to Leer. "You saw naked men running past with guns and artillery on their way to the battle," she says. "We could hear gunfire in the distance." By then, the team had 1400 patients in Duar and another 600 in Leer. MSF decided to evacuate Duar. The plane landed at sunset and was prepared to take off at 4 a.m. Jill began writing instructions for the Nuer staff to carry on the hospital alone. Thousands of tribesmen stood on the runway. She expected bitterness at the desertion and even to be physically attacked. Instead, the Nuer sacrificed a cow to thank her.

The Nuer, named Jill "Chortnyang," the 'brown cow without horns,' because they knew she hated violence. Sjoukie, a pragmatic and cheerful slender blonde, became "Biethyang," a great cow with red and white spots. The MSF plane became "Nyabobka," the blue cow, because of the blue stripe that ran along its fuselage and because the Nuer knew that it brought the medicine that was saving their lives. Says Hesselink,"When the Nuer give you the name of a cow, you know that you have done something right and that they think you are pretty exceptional."

In February 1992, MSF received reports of barges carrying troops on the river near Duar. By then, Jill was trying to cope with simultaneous outbreaks of meningitis, measles, and at least 900 patients suffering from kala azar.

A plane was diverted to evacuate the team. The aircraft, built to carry seven passengers, took off with 11 on board. Jill remembers sitting on the floor of the plane squeezed in between the other passengers, tears steaming down her face as it roared down the field and took off between rows of banana trees. She could not get the images out of her mind. "I kept seeing thousands of people standing at my tent, saying 'I am dying, Jill, what do I do?"

In January 1994, Jill was working until 11:30 p.m. in a tukul processing blood tests for kala azar. Gunfire erupted in the camp and a woman threw herself on top of Jill. She had the mouth of her baby jammed against her breast to keep him quiet. A three year old child outside the hut had been shot in the back, his intestines splayed across the ground. Jill tried to operate, but it was hopeless. The next morning, MSF diverted a plane to pick up the doctors. When it landed, soldiers suddenly appeared, scattering the Nuer in panic.

Jill recalls being so exhausted that she was nearly oblivious to what was happening. The soldiers, it turned out, were guards sent to protect the plane. They stopped in Ler so that a tube could be inserted in the chest of a wounded villager. Then they went on to Nairobi. Jill and Sjoukie took two weeks off to climb Mount Kilamanjaro. Jill suddenly realized that she could no longer sleep in a room alone. Yet after four months back in the US, she was back in Africa. She walked into a village, and gunfire erupted again. "I remember crouching next to the wall of a hut," she says," asking myself over and over, what am I doing here?" It turned out that a wedding was taking place in the next village. The local commander was so startled by Jill's reaction that he had the groom placed under arrest. After that, strict orders were issued not to fire any weapons when Jill was around.

Her biggest problem was a sense of personal helplessness. "I remember someone saying,'Don't worry, Jill is here,'" she says. "But I still couldn't do anything." In fact, she was doing everything. "She did not just treat patients," says Marilyn McHarg, the current country manager for MSF-Holland in Nairobi. "She designed the protocols and the system for the treatment." Just finding enough drugs was a problem. Marilyn McHarg remembers scrounging Pentostam on several continents.

"We found some in Canada and some in Belgium," she says. "Walter Reed hospital had only 20 bottles."

And kala azar, itself, was not the only problem. One day the neurotoxic effects of the Pentostam drove a patient mad and he threw a spear through another man's chest. Jill operated in the open and saved the man's life. Then she and Sjoukie operated on a man so riddled with tropical ulcers that his bones were exposed. A UN official had to turn away, unable to look.

Johan Hesselink remembers just having taken off from Niemne at 6 p.m. as the sun was setting, and getting a call from Jill ordering him back to the field because a woman had complications in childbirth and she didn't have the proper equipment. "I told her it was crazy. It was too late. We would crash," says Hesselink. "She made me do it anyway." At Leer, the Nuer lit fires along the runway so the plane could land in the dark. Hesselink flew back to Niemne the next day with the mother and two newborn twins. Cheering crowds stood along the runway as the plane landed. "Jill really cares," says Hesselink, "but we are in this business to care."

By late 1995, it looked as though the epidemic in the south Sudan was beginning to enter its endemic phase. Jill and the MSF staff had treated more than 20,000 patients. Once treated, they were likely to remain immune to the disease.

The price of stopping the epidemic was high in human terms as well as the more than $1 million a year that MSF-Holland poured into the operation. Of 70 Nuer and Dinka nurses trained by Jill and the other MSF doctors, more than 75% came down with kala azar. Five lost children to the disease. Jill tested positive to the parasite herself. A skin patch produced a scar 40 millimeters long, when 5 millimeters indicates infection. But the disease never materialized.

With the crisis coming increasingly under control, MSF and other relief organizations based in Nairobi began to rethink their role in Sudan. The "hands on" approach of providing medical aid directly to Sudanese is now coming under criticism for building a dependency on outside help. The new approach calls for outside agencies to step back and let the Sudanese develop their own resources. In this new climate, some see Jill's eagerness to help as almost counter productive. Hesselink says that in 1995-96, Jill faced a brief mini-revolt by other expat staff members who insisted that patients only be seen during normal working hours. When Jill continued to see her own patients after hours at night, she was ordered to stop and bluntly informed that she would be sent home on the next plane if she continued to violate the new rules. She was briefly banished to Nairobi until MSF recalled its country director and let her go back to practicing medicine.

But the atmosphere has clearly changed. A few weeks ago in Duar, when Jill examined a baby dying of tuberculosis, the rest of the MSF team balked at providing treatment even though there was medicine to save its life. The team, headed by a Kenyan lab technician argued that it needed two weeks to launch a comprehensive TB program and that it could not afford to make an exception just for one child who was dying. It was the kind of argument that Jill Seaman has trouble accepting. "In two weeks," she said gritting her teeth, "that Baby will be dead." But a tense three hour meeting of the MSF staff voted against making any exceptions to its schedule--even if that meant condemning a child to die.

The "hands on" vs. "hands off" issue is a hot topic in Nairobi, and it is obvious that few expats can keep up the frenetic pace of someone like Jill Seaman. "Doctors have a right to sleep too," says Stephanie Maxwell, MSF's current medical coordinator in Nairobi, who holds a graduate degree in nutrition. "There are doctors who have been in a post for six months and are convinced they are doing a great job, and then Jill comes along, and in comparison it looks like they haven't done anything." But the issue of doing more than emergency medicine is something that relief managers take seriously. Says Marilyn McHarg, MSF's current country representative, "If we pull out of Sudan tomorrow, we would like to know that we are leaving something behind that lasts."

Hesselink acknowledges the arguments, but disagrees with the conclusions. "The problem," he says, " is that the Sudanese don't do more, and people die."

The Nuer are clear on where they stand in this debate. Chief Tongwar, one of the areas most respected head chiefs told a recent council meeting, "Jill is like me. What I think, she knows. " Then he added softly, "If you did not come here, Jill, everyone would have died. We have named many of our daughters 'Jill,' Now we will also name our sons, 'Jill.'"

When Chief Tongwar had spoken, Chief Elizabeth, spokeswoman for the women of Nhiadhiu stood up. "No other doctor came to us," she said,"only you, Jill."

As long as she is allowed to continue, Jill Seaman shows no sign of taking a step back in confronting human misery. "We all make choices," she says,"sometimes you can decide to do one thing, and to do that one thing really well." Marilyn McHarg, MSF's current country manager, seems to appreciate Jill's special talents and has now assigned her, Sjoukie De Wit and another doctor to a flying satellite team that roams from village to village treating kala azar and TB. TB is now a special problem because kala azar has so weakened the Nuers' immune systems that the follow on infection is often fatal. In August, Marilyn dispatched Jill to Ethiopia to survey a new outbreak of kala azar. She is also working on a pilot project to introduce a drug for kala azar that will cost a tenth the price of Pentostam.

But it is really the work with patients that captures Jill. A few weeks ago, she set up a new camp in Manenjang, where the airstrip was so overgrown that the pilot was terrified of landing. On her own once again she seemed in her element. There was no one to hold her back from healing the sick. That night, a woman walked into the new camp with her 11-year old daughter near death from kala azar. Jill shook her head. "She has extreme respiratory distress," she said. But against all odds, Jill tried to save her anyway. At midnight, Jill was rummaging through the tent looking for drugs to resuscitate the girl. In the morning, despite the efforts, the girl was dead. The mother squatted next to the tukul wailing. Her right hand raised trembling in the air and then she grasped her thigh as though desperately trying to hold on to her own body. She repeated the gesture over and over. In the immensity of her grief, academic discussions of relief strategies in Nairobi seemed nothing less than a trivialization of human destiny. "This was her last child,"Jill said. Then Jill squatted next to the mother and whispered in Nuer, "My heart is in the earth."

The next night at around 10 p.m, a loud flailing sound erupted outside Jill's tent. A mother was desperately trying to revive her 8-year old son in the last stages of cerebral malaria. As I watched, I thought this would be another hopeless case. The boy was slipping into and out of consciousness. The mother, pounding on his chest, looked as though she would beat him to death in her desperation to keep him breathing.

Jill bent down to get closer. A swarm of mosquitoes descended on her ankles and arms in an African feeding frenzy. Ignoring her own discomfort, she prepared an IV. The boy's blood pressure was so low and his arms were so thin that she could not find a vein.

With a Nuer nurse holding the boy tightly, she jabbed the IV into his arm, and then dissatisfied, pulled it out. "It's not right," she explained. The boy writhed in agony. Calmly she inserted the needle four or five times more before she was finally sure that she had it right. At 2 a.m. she ducked back into the boy's tukul to give him more medicine. In the morning, by some miracle he was alive and smiling. The Nuer mother beamed at Jill, and then she was gone. Jill sat down at the camp table outside her tent, poured herself a cup of tea and began preparing herself for her morning patients.

The next big epidemic in Sudan looks like it will be sleeping sickness. The trypansosome parasite that causes it is a distant cousin of kala azar. Infection rates in some villages in Equatoria just south of the Western Upper Nile are already running at 20%. Experts question whether it can be treated without hospitalization--an option which because of the enormous numbers is clearly out of the question. It is the kind of impossible field medical problem that is tailor-made for Jill Seaman, and she has already indicated that she'd like to get involved, if the decision makers in Nairobi get around to asking her.

In the meantime, Jill has the consolation of knowing that she has saved a tribe in Africa as well as its way of life. "We used to fly over here and there were no tukuls," says Johan Hesselink. "Now there are tukuls everywhere. These people have come back because they see a future. That is what life is about." It is no small achievement for an unassuming American girl from Moscow, Idaho.

--Southern Sudan, 1997