WAR IN THE MIDDLE EAST: ANYONE REMEMBER BEIRUT? By William Dowell |

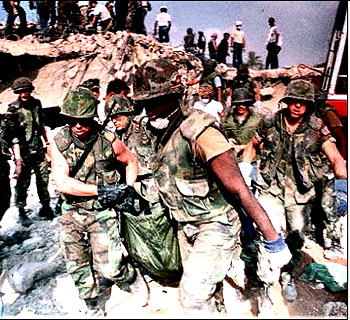

US Marines remove bodies after a 400-lb truck bomb killed 241 US Marines, sailors and servicemen in 1983 US Marines remove bodies after a 400-lb truck bomb killed 241 US Marines, sailors and servicemen in 1983 |

It is impossible to listen to the Bush administration’s confident predictions about a freer, democratic post-Saddam Iraq and not experience a flashback to Lebanon in 1983. While reporting on that long-forgotten crisis, I spent an evening in a U.S. Marine foxhole on the perimeter of Beirut’s beleaguered airport. The Marines happily demonstrated the latest technology — an infantry ground radar that could pick up the precise position of a sniper by tracking a single bullet, computer aimed mortars that could target an individual enemy soldier, and night-vision equipment that turned the surrounding hills into daylight.

"I hope they do attack," a youthful Jarhead told me. "I want to kill Arabs." I didn’t use that quote. When he said it, I recalled the shattered billboard outside Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport, and its slogan, "Pan Am Makes the Going Great!" It was early spring in 1968, and smoke was billowing from the burning buildings behind the crazy sign. Terrified American GI’s huddled next to the walls of the terminal building, never knowing when the next stray bullet or mortar would take someone out. The casualties were running at 500 to 550 Americans dead each week. It was a war George Bush, Paul Wolfowitz and Donald Rumsfeld never quite managed to see up close. Colin Powell did, and he may be the only one in this administration who really knows what he is talking about. I knew when I heard that young Marine talk that he really did not know what he was saying.

The day after my night with the Marines, I caught an impromptu press conference on the tarmac of Beirut airport with the then-Chief of Naval Operations. "We are experimenting in using military power to solve political disputes," said the admiral. "We are going to start to look where else we can do this in the world. You could say we have taken the high ground." I was surprised at both the concept and the image.

"Pardon me, admiral," I said. "I don’t know if you see these mountains surrounding us. They are filled with artillery that is pointing down at this spot where we are standing. I don’t see how you can say that we have taken the high ground?"

"Well," he said, "it is just a figure of speech." A few months later a truck with a 12,000-lb. bomb drove past Marine sentries and blew up the Marine barracks at the airport, killing 241 Marines and wounding another 80. Soon after, President Reagan withdrew U.S. forces from Beirut. Colin Powell remarked later, "What I saw from my perch in the Pentagon was America sticking its hand into a thousand-year old hornet’s nest."

Ronald Reagan was not wrong in pulling out of Beirut. Nothing there was worth the cost in American lives. Bill Clinton was right to withdraw from Mogadishu in Somalia after the events recounted in "Black Hawk Down." In both cases, retreat was the correct choice. But the hasty U.S. withdrawals sent a message: if you can kill enough Americans — not too many, but just enough — the United States will turn tail and run.

Saddam Hussein certainly got that message, and it was one of the reasons he overstepped himself in Kuwait and Desert Storm. But our real mistake was not in retreating; it was in getting involved in the first place. It was the careless way that our pride and overconfidence led us into complex conflicts that we barely understood and that we would ultimately discover were not worth dying for.

After Beirut, I covered Desert Storm and drove into Kuwait less than 24 hours after the Iraqis had pulled out. Anyone who knew combat knew that the real danger in Kuwait was the false conclusions it would inspire in Washington. The ease of the victory was not natural, and it was bound to generate a false confidence about war. Unlike Iraq, Kuwait is small and literally as flat as a tabletop. Moreover, in Desert Storm, U.S. forces were merely convincing a marauding foreign army to go home. They were not fighting soldiers in their own villages or on their own terrain. More important, they were not fighting them after the opposing forces had seen us attack their homes with cruise missiles or dismiss their families and relatives as collateral damage.

In this war we seem to have forgotten something important that some of us learned in Vietnam, but which some members of the administration haven’t really grasped yet. It is that in war, the victor often suffers as much psychological damage as the vanquished. We control territory and impose our will, but there is something in us, something about who we are, that is forever changed — and not for the better.

George Washington understood that when he cautioned against foreign entanglements. We can see its effect already. We look the other way when it is suggested that a terrorist subject might be tortured by a third world country known for being less squeamish than we are. We deny due process of law to our own citizens. We are beginning to target new immigrants according to their ethnic identity and religion. We use promises of foreign aid to buy votes on the U.N. Security Council, and then talk about instilling democracy and freedom of choice. And we haven’t even begun.

With any war, getting in is the easy part, extricating yourself is another matter.

A few years ago I asked the defense minister of Qatar why everyone was so upset about Iraq. "It’s simple," he said. "If Iraq breaks up, it will be like Beirut, but this time with ballistic missiles."